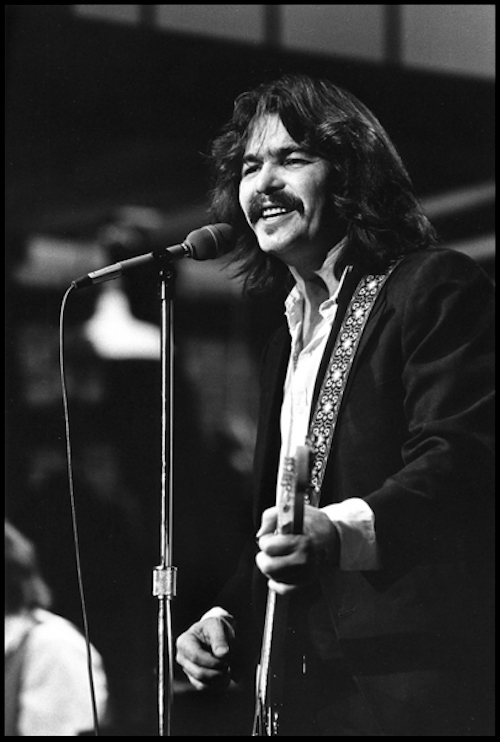

Some of you have wondered about this very weird guitar that shows up from time to time in photos of me. Meet the Twangoleum!

I found the Twangoleum hanging in the window of an antique shop in Seattle, on Aurora Avenue in 1969. I nearly drove off the road! Unfortunately the window faced west and got hot in the afternoon. The only case was a green felt bag, and the instrument was pretty warped. Strung up with steel strings heavy enough to support the Brooklyn Bridge. The family who had sold it to the dealer said their father brought it home from Europe at the end of WWI!

It’s had a few periods of being played a LOT. The “alligator tail” prevents it from being barred up the neck, and the intonation was off from the warp in the face. The saddle has been relocated to try to deal with the intonation. In 1973 I handed it, on permanent loan, to Andy Cohen, who was playing a lot on the street. We were both living in Syracuse at the time. He had fallen madly in love with it and eventually gave it its name. Thereafter, I got occasional missives describing their adventures, plus a huge poster touting “A. Morris Meltzer-Cohen, the Twangoleum King” complete with a great photo. He said, “There’s only one of it, so I might as well be king of it.” He played it on the street for years, and it did its job. Lots of people stopped to listen! I had told Andy that if he were ever done with it, he should give it back. I had moved home to Bellingham, Washington state, right after I handed it to Andy. One night around 3 AM I got a phone call that began, “I’m done with it, and I’ve got it a ride.”

“Huh? What? Who?” Well, once we sorted out what “it” was, I learned that the Twangoleum was headed for Port Townsend, Washington. My benefactor stopped in Bellingham on the way to bring my baby back home.

It’s history with me has a lot of connections with Port Townsend. I think Rick Ruskin had it for a while next. He’s a great player from Seattle. I have a vague recollection of Elizabeth Cotten playing it during one of her visits, during the late 1970s. It’s gotten around!” Kerry Char of Portland did a restoration that included removing the whole fingerboard and sliding it up towards the headstock until it played in tune again.

John Jackson whittled it a new bridge pin out of a holly twig one morning at the first CENTRUM Blues Workshop in Port Townsend. The old pin had mysteriously disappeared and John wanted to play my baby! John leaned off the porch, broke a twig off a holly bush, and pulled out his pocket knife. The Twangoleum was passed hand-to-hand among a circle of old blues players, who were delighted to feel the alligator tail vibrate against their chests. It takes care to keep from banging the back of your fretting hand against that tail though. Backs of hands have no padding, and it hurts!

We just took the Twango back to Port Townsend for my brother Joe Breskin’s 72nd birthday concert. It never made it as far as the stage, but was passed hand to hand around the audience (lots of players) while we waited for the concert to get underway. (Music actually starts at about 27 minutes in on that concert link.)